FROM THE UNDERGROUND

Loosely based on Dostoevsky's 1864 novella 'Notes From The Underground', Wherein the narrator's solitary ruminations and attempts to unravel the fabric of societal tradition proves only to unravel himself.

Similarly, From The Underground is an outsider's attempt to deconstruct what's seemingly ordinary and preordained, with focus on habit, ritual and transgenerational patterns.

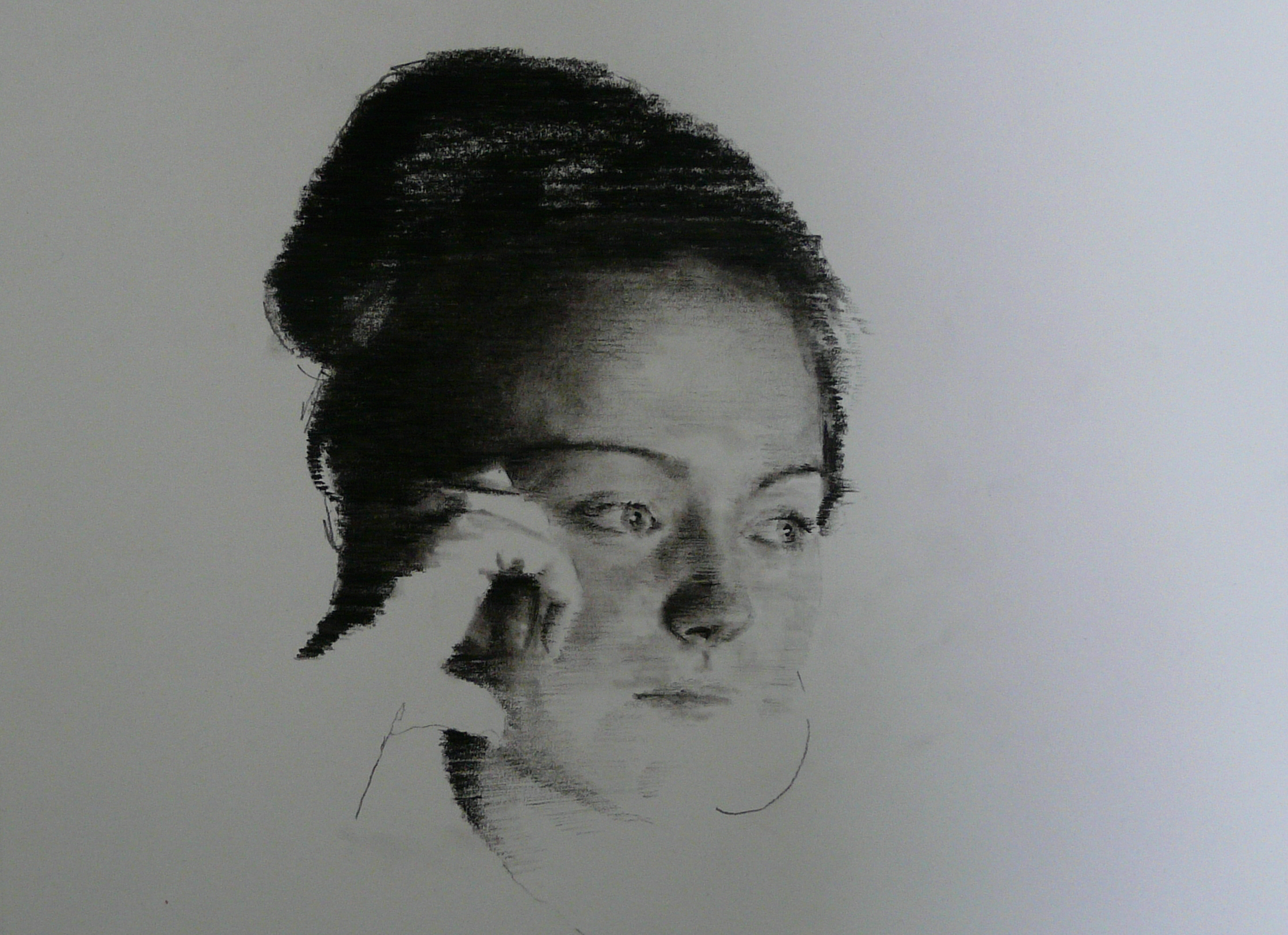

A voyeuristic glimpse at domestic discord, 62 Malus Avenue, could be described as a mood-scape or an anti-portrait and by that token is, perhaps, best defined by what it is not. While some of the characteristics of portraiture are present, here they seem to betray the tradition. Lighting, for example, usually compliments its sitters, but here the light seems to scrutinise the subjects. Despite the omnipresence of the naked light, it does little to provoke derision from the viewer but rather engenders our sympathy and maybe even a certain guilt for observing this moment of misbegotten intimacy.

This sense of an ill-conceived arrangement is echoed throughout the composition, from the disharmony of the colour schemes to the decor which verges on the garish, like a stage set or an IKEA showroom.

These bold choices seem to disclose the female character's urge to cultivate her environment, despite a lack of means and maturity. This, however, is not a malady reserved solely for our ingénue, but rather a symptom of a society-wide tendency to imitate or to content ourselves with a flimsy replica of the original.

Yet for all its contrivances and frailty, there is one theme at the beating heart of the painting that feels solid in comparison to its surroundings: the symbiosis between mother and child. Cradled in maternal blues, the child disappears into the mother's form, mirroring the solidity of Eastern Christian icons. The icon of mother and child appears to be the symbolic centre of the painting, from which all other symbols seem, comparatively, fragile. These other symbols of supposed femininity throughout the painting seem to be precariously positioned, threatening collapse. This adds to a sense of foreboding that steals through the room, begging the question: can the centre hold?

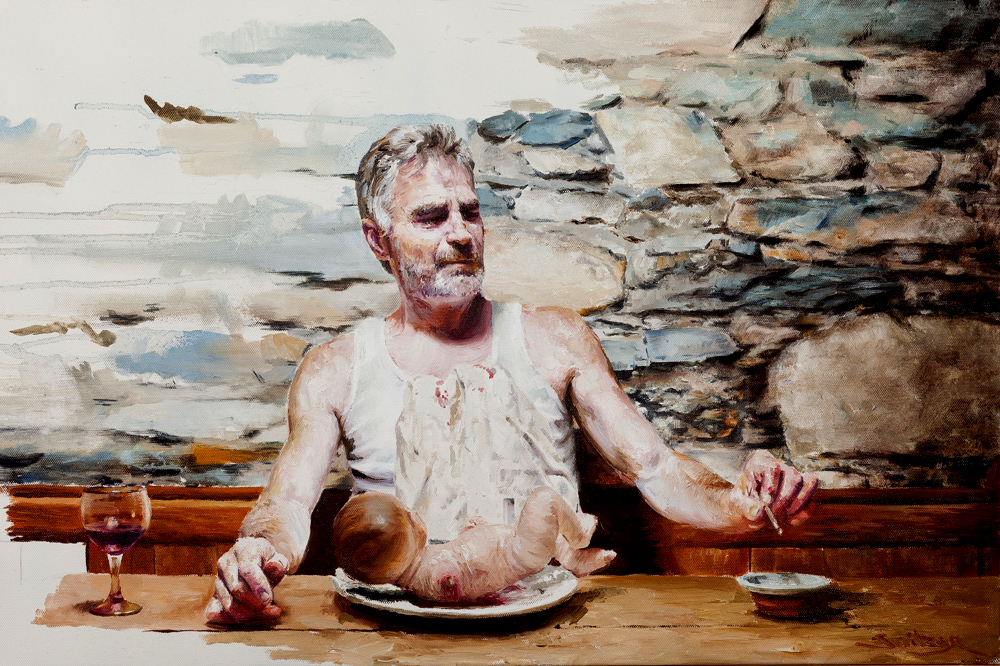

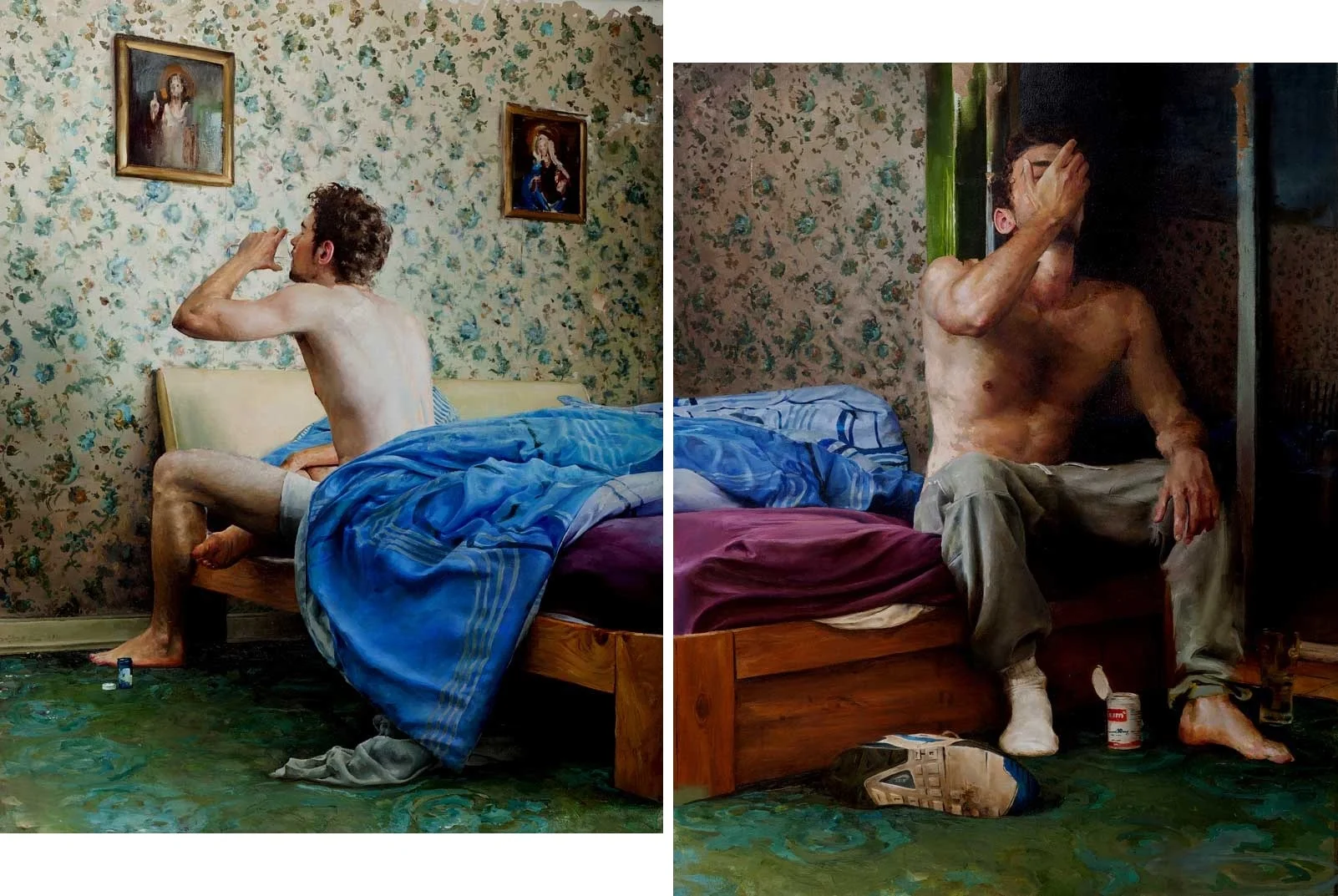

A divisive image - for obvious reasons - Kristiania is, in fact, a painting about the birth of expressionism, despite perhaps, its immediate evocations of mythological savagery.

The painting takes its name from 'Kristiania', (current day Oslo), the birthplace of Edvard Munch, who is considered one of the founding fathers of expressionism.

Expressionism itself seems to be at odds with its northern European birthplace, as do the individuals who pioneered the movement.

Munch, like many other expressionists, was haunted by his father's religious fanaticism. A childhood marred by rigid devotion to straight lined piousness, Munch turned his back on the doctrine of his youth and on Kristiania itself. Without this compulsion to secede, and his zealous dedication to a new church of softened lines, modernism would have never known one of its leading apostles.

However that's not say that Kristiania is an outright damnation of the old guard. In spite of the central character's strong presence it's questionable whether he is priest or participant in a ritual that spans many cultures and generations.

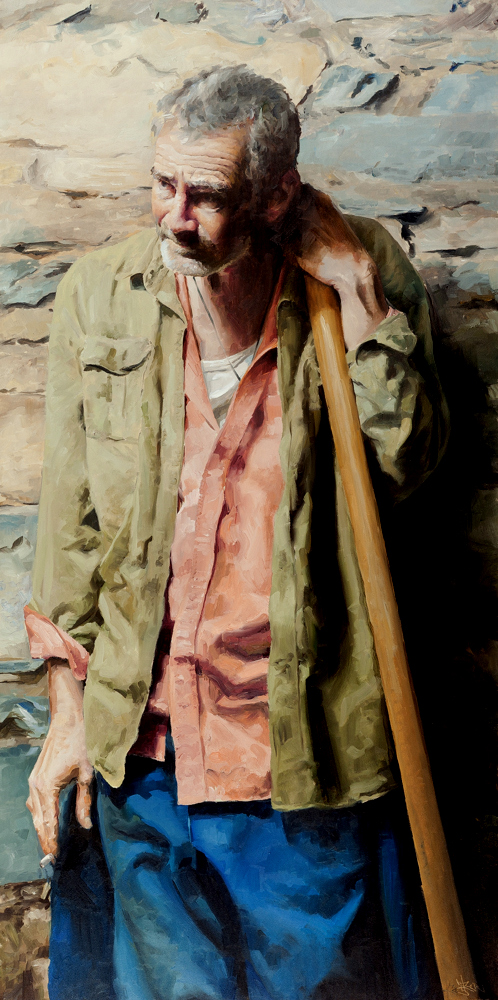

Sisyphus, is a response to Albert Camus' 'The Myth of Sisyphus', a crucial text of early existentialist thought, where the dichotomy of whether it is noble or foolish to continue to toil in an absurd world devoid of order and meaning.

In the painting this concept of the 'absurd' is stretched even further by personifying the Sisyphean archetype as a grave digger. A trade where mortality, you might imagine, is the preoccupying thought of the entire endevour. Furthermore, the very idea of digging a grave for another on a daily basis only to one day retire to your own seems to epitomise the absurdity of vocation.

Like Camus explores in his book, man is seldom made privy to the 'absurd' and only encounters it in moments of quiet reflection. Here our character seems to be caught in one of these moments of contemplation, questioning like us, whether or not his task is a noble one and moreover whether his dutiful predicament can in some way provide solace in an increasingly absurd world.